CHAPTER VI

A MISCELLANY RELATED TO NUCLEAR LESIONS

GAS IN THE NUCLEAR SPACE

Knutsson in 1942 was the first to report the presence of gas observed in x-rays of abnormal intervertebral discs. He described it as the “vacuum phenomenon” and stated that “it is pathognomonic for disc degeneration from the radiologist's viewpoint”'.

The “vacuum phenomenon” is seen only occasionally in routine x-rays. Actually it is gas drawn into the nuclear space over a long period of time, by the vacuum caused by the change of the nucleus from mesenchymal jelly to the smaller volume of fibrous tissue. It is a slow process, and one that does not have much success. The space must be taken up by pulling the lamellae of the annulus inwards, and by the gradual narrowing of the intervertebral space which follows a nuclear lesion.

We arranged a series of cases in which heavy traction in the order of two hundred pounds of pull was applied for as long as an hour as directly as possible to the involved intervertebral disc. X-rays taken while the traction was maintained showed that we did not succeed in drawing demonstrable gas into the nuclear space of any injured intervertebral disc. We concluded that the annulus, for all practical purposes, is air-tight and that the nuclear space in an injured disc probably absorbs gas at about the same rate that a new automobile tire loses air. From these experiments we concluded too that it must be impossible for any nutrition to reach the nucleus, as long as the annulus has not been eroded almost to the point of herniation of the nucleus.

We repeated these experiments on six patients who were proceeding to operation. In only one case were we able to demonstrate that gas had been drawn into the nuclear space. At operation in this case it was found that the fibrous nucleus had just worn its way through the last lamella of the posterior annulus. A potential vacuum had been created by the traction and gas, presumably available from adjacent capillaries, had been drawn into it. In the cases in which no gas had been drawn into the nuclear space it was judged at operation that at least two intact posterior lamellae remained.

These experiments showed that in cases in which gas is observed in the nuclear space an airway has probably been established between the spinal canal and the nuclear space. Therefore, if gas is observed in a nuclear space operation to remove the nucleus of the affected intervertebral disc is almost certainly unavoidable.

THE UNSTABLE VERTEBRA

Knutsson1also reported that in fifteen per cent of his cases that had been diagnosed as disc lesions abnormal movement of the vertebral body above the affected disc was demonstrated by x-rays.

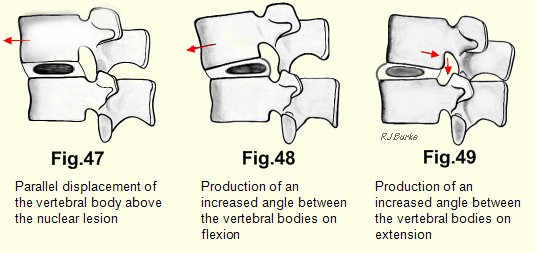

Hirsch2 followed this work by removing complete lumbar spines at autopsies and mechanically flexing and extending them. He observed that “if the structure of an intervertebral disc has been modified there arose changes in the path of movement of the vertebra above.” He demonstrated parallel displacements and the production of an increased angle between the vertebrae on flexion and extension. In every case the displacement was of the vertebra above the abnormal disc (Figs. 47, 48, 49).

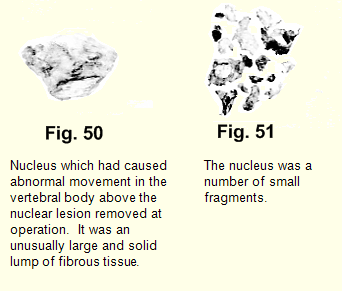

Where no dislocation could be demonstrated the nucleus was found to consist of several or a large number of smaller masses (Fig. 51 below)

On reviewing the cases which demonstrated the abnormal movement, we found that their histories were comparatively short

We thought that the work of Knutsson and Hirsch might be an aid in the accurate localization of the nuclear lesion prior to operation, so for two or three years we had lateral x-rays taken in the extremes of flexion and extension. We found convincing abnormality of movement in only a very few of them. In each of the cases in which abnormal movement was seen on x-rays we discovered at operation an unusually large and solid lump of fibrous tissue (Fig. 50). We concluded that it was this solid mass between the vertebral bodies acting as a wedge, which caused the dislocations. Where no dislocation could be demonstrated the nucleus was found to consist of several or a large number of smaller masses (Fig. 51).

On reviewing the cases which demonstrated the abnormal movement, we found that their histories were comparatively short - only a few years from the first attack of “lumbago”. Enough time had not elapsed for the vertebral bodies to grind up the fibrous mass into smaller pieces. After the operative wound had healed clinical examination showed the painless spine to be perfectly stable and x-rays showed no abnormality of movement. Therefore, spinal fusion is not indicated in cases of “unstable vertebra”.

PSEUDO-SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

This is the term that the Swedish orthopaedic surgeons have applied to the abnormal movement of the vertebral body above the disc lesion. If an x-ray film catches a vertebral body in the dislocated position it is quite likely to be diagnosed as spondylolisthesis-. Additional lateral x-rays in flexion and extension should be taken to see if the vertebral body changes position with change in posture. This precaution will save many patients from an unnecessary spinal fusion. If surgery needs to be done, all that is necessary is the excision of the affected nucleus, which is the one below the vertebra that has shown the abnormal movement. After that the joint is stable and painless. This, by the way, is not a “herniated disc”. If the nucleus had herniated there would have been no abnormality of movement.

Spinal fusion is not indicated in the treatment of “pseudospondylolisthesis”.

SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Spondylolisthesis is the forward displacement of one of the lower lumbar vertebrae upon the one below or upon the sacrum. It is usually the result of failure of union between the body and the neural arch, subsequent to a developmental defect in the laminae or pedicles.

The deformity has also been reported in thoracic and cervical spines. In these regions it should be remembered that one may be dealing with an example of “the unstable vertebra”.

On observing the striking x-ray appearance, it is natural to attribute the patient's pain to the deformity; but it is an incorrect assumption. The congenital deformities of orthopaedic surgery are notably painless, and spondylolisthesis is no exception.

If a continuing deforming factor is exerted during growth, the deformities of orthopaedic surgery increase as long as the patient is growing. They do not increase further after growth has ceased. A good example is scoliosis following poliomyelitis. The deforming factor of muscle imbalance remains. Deformity increases as the child grows. There is no further increase in the deformity after growth has stopped. So it is probable that in spondylolisthesis the deformity slowly increases as the patient grows. After growth has ceased there is no further increase in the dislocation. The joint is so stable that it cannot be reduced nor can it be increased except by the application of force so great that the patient would be unlikely to survive it.

If the dislocation, or any increase in the dislocation in spondylolisthesis could be attributed to an accident, then about ten days after the accident x-rays would demonstrate reactive changes in the neighbouring bone. I have not seen these changes. The question also arises - why is it that symptoms do not usually appear in spondylolisthesis much before the age of thirty, long after growth has ceased, if the deformity had been increasing during the growth period? The answer-is that the deformity is not the cause of pain.

In 1940 at a meeting of the American Medical Association, Walter Dandy3 stated that “spondylolisthesis is merely an incident in the syndrome of intervertebral disc lesions ... spinal fusions are never indicated either for spondylolisthesis or for defective intervertebral discs”. He was vigorously attacked for this stand. One critic said that “it is difficult to consider seriously any part of a discussion which is based upon so blatant a misconception of its its subject! ”

We now believe that Dandy was right. It is notable that symptoms attributed to spondylolisthesis usually do not appear before, the age of thirty, though cases have been reported as young as the age of five. If the dislocation in spondylolisthesis is slight, say less than one-quarter of an inch, then the pain may be attributable to a nuclear lesion of the involved intervertebral disc. However, care must be used in assessing these cases. If the dislocation is much greater than that it is likely that the nucleus and most of the annulus has, long since, been destroyed and that these two vertebral bodies are solidly bound together by fibrous tissue and sometimes by bony union. The joint is stable, the joint is painless, but the striking x-ray appearance may deceive the doctor. The patient should be carefully examined with the strong suspicion in mind that the pain is all arising from the intervertebral disc above the spondylolisthesis.

Spinal fusion has no place in the treatment of spondylolisthesis.

THE NARROWED INTERVERTEBRAL DISC

The narrowed intervertebral disc reported on x-rays is another radiological source of confusion. It indicates a nuclear lesion that has been present for many years, but the patient's disability should not be automatically attributed to this intervertebral disc.

The mesenchyme enclosed by the annulus maintains the separation of the vertebral bodies and even after injury the fibrous nucleus with the annulus, still is a considerable influence in this direction. Many years pass before the fibrous nucleus becomes broken up and the annulus flattens, so that narrowing of the intervertebral disc space occurs. By that time the nucleus may have become broken' up into small pieces which are not giving any trouble. Again, if operation is being considered, one must be alert to the possibility that the intervertebral disc giving trouble is a neighbouring one.

IMBIBITION

Charnley4 demonstrated experimentally that the nucleus after removal from the body, would take up fluid from four times hypertonic saline. It swelled greatly, while the annulus remained undisturbed. He wondered whether under certain conditions, the disc might acquire an abnormal amount of fluid and thereby achieve an abnormally high internal pressure. He thought that such an attack of nuclear hypertension might cause “lumbago,” and a spontaneous protrusion. Thereafter, some slight injury might complete the bursting of the annulus and the subsequent impingement on a nerve root would convert the picture from one of lumbago to sciatica.

This theory found little favour with other orthopaedic surgeons. Hendry5 wrote that a gel exhibits the phenomenon known as imbibition, whereby it can extract water from hypertonic solutions, which is in contrast to the phenomenon of osmosis. He stated firmly that there is no possibility of major degrees of hydration ever occuring in a gel in the human body during life, but that it is interesting to note the enormous force that can be brought into play by the imbibition mechanism. He observed that this force is responsible for the swelling of slippery elm; for the extraction of water from saturated salt solutions by dried gelatin; for the continued hydration of the cactus in spite of the osmotic pressure exerted by dry, salty soil; for the ability of mushrooms to lift paving stones and dried peas to split rocks; and for many other familiar phenomena.

Armstrong6 with some acerbity, wrote that one simply cannot say that the cause of backache is that the nucleus swells up and bursts.

Hirsch and Schajowiecz7 objected to the belief that variations in the water content of the normal disc give pain. They pointed out that the attempted injection of saline solution into a normal nucleus even under pressure does not cause pain, and further, that no evidence has been produced that variations in the water content arise in one and the same disc within a limited period of time.

Our objection to this theory is that imbibition functions under conditions that are impossible in human physiology. There is no equivalent in the living body to dry, salty soil as a major factor in the internal environment. Localized calcified areas are isolated and do not count. They are desert islands in the metabolic stream. Further, if conditions arose whereby one normal nucleus swelled up and exerted such enormous pressures, surely all the nuclei would behave similarly. Then the patient would go to his doctor and announce that he had grown six inches yesterday, and the doctor would be able to prophesy that he would soon suffer from lumbago, and that later he would have sciatica as well.

TERMS WHICH SHOULD BE DISCONTINUED:

“Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge.“ (Job, 38:2)”

There are several terms used in describing intervertebral disc lesions which are inaccurate and objectionable.

1. DEHYDRATED DISC

It has been observed by a number of writers that the water content of the normal nucleus is much greater than that of what is too often described as the “degenerated disc.” The difference is simply that which exists between mesenchyme and fibrous tissue (or more accurately the mixture, largely of fibrous tissue with lesser amounts of fibrocartilage and cartilage) into which the nucleus changes.

2. DEGENERATED DISC

To degenerate is to decline to a lower type, to become debased, or degraded. The nucleus which is causing trouble has moved up the evolutionary scale from a primitive to a more specialized tissue. It cannot, therefore, be described as “degenerated.” The discs in the older age group, in which the nuclei could properly be described as degenerated, give trouble only very infrequently.

3. PROLAPSED DISC

The term “prolapsed disc” is similarly inaccurate. It means that the disc has slipped forward, or downwards out of place, and is reminiscent of the “slipped discs” of the sports' pages. Dislocation of an intervertebral disc does not occur except by extremely violent and inevitably fatal injury.

4. RUPTURED DISC

The ruptured disc implies that it has burst or broken, which for all practical purposes, does not happen.

Hirsch8 used the term “ruptures of the intervertebral disc” in a different sense. He did five hundred autopsies on the lower lumbar intervertebral discs in patients who had histories of “lumbago-sciatica” and recorded his observations. He described the rupture of individual lamellae in the posterior part of the annulus. He observed that ruptures occurred “in the inside lamellae first and proceeded outwards.”

Actually these “ruptures” are the result of erosion of the annulus by the fibrous nucleus. Hirsch also observed, but without enlarging on the point, that changes were far advanced in the nucleus before any change occurred in the annulus.

5. SPONDYLOSIS

This term means vertebral degeneration. As a diagnosis it defies definition but it is applied loosely to the manifestations of nuclear lesions of the intervertebral discs.

6. ROOT PAIN is a misnomer.

7. “ROOT SIGNS” is meaningless.

PREFERABLE TERMS:

The Swedish orthopaedic surgeons use the terms “stiff neck brachialgia syndrome” or “cervico-brachialgia”“ and “dorsal disc lesions” and “lumbago-sciatica syndrome.” The terms are excellent from a descriptive point of view, but are not, as our diagnostic ideal should be, based on etiology.

THE INEVITABLE TERM

We prefer the term “nuclear lesion” and regard it as being accurate and descriptive. It is actually the change from the soft nuclear jelly to the firm fibrous mass which causes all the trouble.